Gun owners and friends of the Second Amendment are angered by the Trump administration’s continued defense of the restrictions and prohibitions on selective-fire and full-auto firearms.

District court decisions in two cases, United States v. Justin Bryce Brown in the Fifth Circuit and United States v. Tamori Morgan in the Tenth Circuit, have held machine guns are protected by the Second Amendment and the restrictions on them are unconstitutional.

The administration’s position is understandable: No Republican is going to stake their seat on even relaxing the laws governing citizen ownership of machine guns. The hoplophobes would eat them alive.

The attorneys arguing the government’s side rely heavily on the late Antonin Scalia’s opinion in District of Columbia v. Heller. Scalia expanded the variety of guns protected by the Second Amendment by setting a new standard: “In common use for lawful purposes.”

Scalia also wrote the rights protected by the Second Amendment were not unlimited and didn’t cover weapons considered “Dangerous and unusual.”

But Scalia’s definitions are dicta; they are not part in the court’s primary holding, which was to say arms protected by the Second Amendment can’t be banned. Dicta are not binding on other courts and don’t establish a legal precedent.

That portion of Scalia’s opinion was likely intended to correct an oversight in Justice James McReynolds’ majority opinion in United States v. Miller.

In reversing a lower court ruling in a case involving a short-barreled shotgun, McReynolds wrote: “In the absence of any evidence tending to show that possession or use of a “shotgun having a barrel of less than eighteen inches in length” at this time has some reasonable relationship to the preservation or efficiency of a well regulated militia, we cannot say that the Second Amendment guarantees the right to keep and bear such an instrument. Certainly it is not within judicial notice that this weapon is any part of the ordinary military equipment, or that its use could contribute to the common defense.”

While sawed-off shotguns might not be suitable, machine guns, including the M1918 Browning Automatic Rifle and the Thompson submachine gun, were definitely suitable and had been in National Guard armories for years. In fact, National Guard and police armories were where gangsters usually got the machine guns they used.

Very few people in the pro-Second Amendment community remember Sonzinsky v. United States, a 1937 decision affirming the National Firearms Act as a revenue law well within Congress’ taxing power described in Article 1, Section 8, Clause 1 of the U.S. Constitution.

In Justice Harlan Stone’s majority opinion, the court held: “Every tax is in some measure regulatory. To some extent, it interposes an economic impediment to the activity taxed, as compared with others not taxed. But a tax is not any the less a tax because it has a regulatory effect and it has long been established that an Act of Congress which, on its face, purports to be an exercise of the taxing power is not any the less so because the tax is burdensome or tends to restrict or suppress the thing taxed.”

The National Firearms Act of 1934 has never been upheld as anything but a revenue measure. The court’s holding in Sonzinsky was affirmed in Miller.

So how does that effect Scalia’s “in common use” standard?

It’s important to remember that machine guns are not all banned at the national level. They must be registered, which requires approval from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives before they can be transferred to another person. What is a ban on machine guns is a prohibition on registering new or previously unregistered machine guns after May 19, 1986. This was the Hughes Amendment to the Firearm Owners Protection Act of 1986, a last-minute “arrangement” between New Jersey Representative William Hughes and New York Representative Charles Rangel, chairman of the committee that handled the bill.

The ATF says there are 175,977 registered, fully transferable, machine guns owned by American private citizens. This figure doesn’t include several hundred thousand owned by law enforcement and other government agencies, which are exempt.

So how does all of this impact Scalia’s “in common use” standard?

When the National Firearms Act of 1934 was enacted, the price of a Thompson submachine gun was $200 or about $4,788 in today’s money. This represented about 21% of a typical worker’s annual pay. With the addition of the transfer tax, the cost would have been about $9,576, or 43% of the average worker’s annual pay. Remember the U.S. was in the throes of the Great Depression; there weren’t very many people capable of shelling out that kind of money for a gun with very limited use.

With the passage of the Hughes Amendment, prices for transferable machine guns skyrocketed.

In the mid-1970s, I was considering braving the gauntlet and buying a new-in-the-box Smith & Wesson Model 76, a close copy of the Swedish Carl Gustav M45 but with a selective fire option. The price was $140.00.

Based on several M76es offered today, the typical price averages about $19,000.

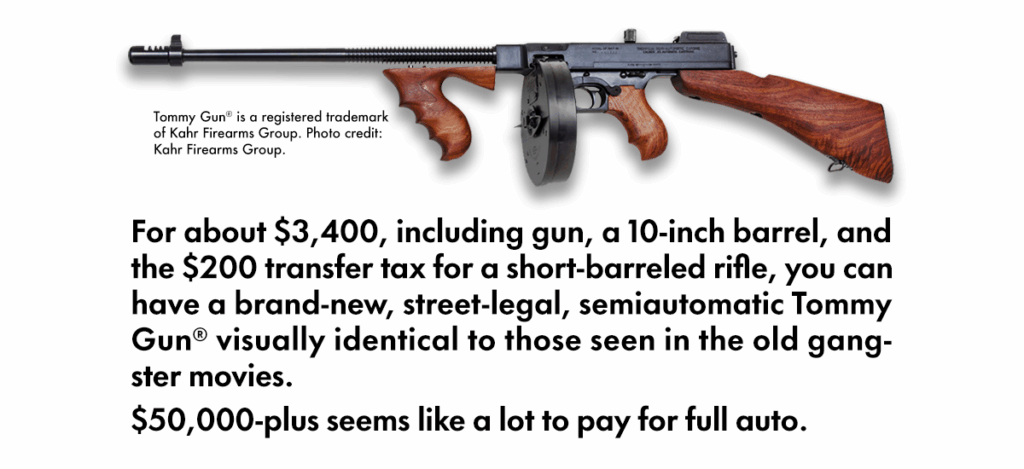

That $200 Thompson? Anywhere from $58,000 to $82,000.

How could machine guns be in common use? The Hughes Amendment froze the number of machine guns citizens could own at 175,997; no more can be added.

This also means machine guns are going to be unusual. Even if every machine gun was owned by a different American, only 0.066% of the adult population would have one. Since there are American machine gun collectors who own more than one, that percentage is even smaller. Are they dangerous? Only if people make them dangerous.

If we go by the requirements set out in New York State Rifle and Pistol Association v. Bruen and look to history and tradition, there are no analogs in either the time around the ratification of the Bill of Rights or the Reconstruction period after the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified.

The current uproar about automatic weapons isn’t even about true machine guns. Black-market switches allowing Glock pistols to be converted to selective fire are the actual issue and, by their very nature, they aren’t going to be controlled by laws because the parts are relatively easy to make if the supply of ready-made versions ever dries up. As we say repeatedly, criminals don’t obey the law.

Incidentally, a benefit of dropping the opposition to the district court decisions in the Fifth and Tenth Circuits would be to eliminate the whole “military” excuse to ban rifles like the AR-15. I am pretty sure gun control zealots don’t realize it’s perfectly legal to own a functional tank or artillery piece so they look pretty stupid trying to ban semiautomatic rifles because they have a pistol grip or flash hider.

Except as noted, all content copyright © 2025 Second Amendment Society of Texas. All rights reserved.

Become a Friend of the Society on Patreon